- Mansa (慢撤山): The term for "seed sowing bag" (撒袋, pinyin: sǎdài)

- Mangzhi (莽枝山): The term for "copper cauldron" (铜鉧, pinyin: tóngmǔ) [note 1]

- Yibang(倚邦山): The term for "wooden clapper" (木梆, pinyin: mùbāng)

- Yōulè (攸樂山): The term meaning "copper gong" (铜锣, pinyin: tóngluó)

- Mengsong Shān (勐宋山):

- Menghai Shān (勐海山):

- Jingmai Shān (景迈山):

- Nánnuò Shān (南糯山): a varietal of tea grows here called zĭjuān (紫娟, literally "purple lady") whose buds and bud leaves have a purple hue.

- Bada Shān (巴达山):

- Yōulè Shān (攸乐山):

- Bānzhāng (班章): a Hani ethnicity village in the Bulang Mountains, noted for producing powerful and complex teas that are bitter with a sweet aftertaste

- Bada Shān(巴達山):

- Wuliang Shān:

- Ailuo Shān:

- Jinggu Shān:

- Baoshan Shān:

- Yushou Shān:

- Kunming Tea Factory

- Pu’er Tea Factory (now Pu’er Tea group Co.Ltd )

- Six Famous Tea Mountain Factory

- unknown / not specified

- Haiwan Tea Factory and Long Sheng Tea Factory[9]

- Dried tea: There should be a lack of twigs, extraneous matter and white or dark mold spots on the surface of the compressed pu-erh. The leaves should ideally be whole, visually distinct, and not appear muddy. The leaves may be dry and fragile, but not powdery. Good tea should be quite fragrant, even when dry. Good pressed pu-erh often have a matte sheen on the surface of the cake, though this is not necessarily a sole indicator of quality

- Liquor: The tea liquor of both raw and ripe pu-erh should never appear cloudy. Well-aged raw pu-erh and well-crafted ripe pu-erh tea may produce a dark reddish liquor, reminiscent of a dried jujube, but in either case the liquor should not be opaque, "muddy," or black in colour. The flavours of pu-erh liquors should persist and be revealed throughout separate or subsequent infusions, and never abruptly disappear, since this could be the sign of added flavorants.

- Young raw puerh:The ideal liquors should be aromatic with a light but distinct odours of camphor, rich herbal notes like Chinese medicine, fragrance floral notes, hints of dried fruit aromas such as preserved plums, and should exhibit only some grassy notes to the likes of fresh sencha. Young raw pu-erh may sometimes be quite bitter and astringent, but should also exhibit a pleasant mouthfeel and "sweet" aftertaste, referred to as gān (甘) and húigān(回甘).

- Aged raw puerh: Aged pu-erh should never smell moldy, musty, or strongly fungal, though some pu-erh drinkers consider these smells to be unoffensive or even enjoyable. The smell of aged pu-erh may vary, with an "aged" but not "stuffy" odour. The taste of aged raw pu-erh or ripe pu-erh should be smooth, with slight hints of bitterness, and lack a biting astringency or any off-sour tastes. The element of taste is an important indicator of aged pu-erh quality, the texture should be rich and thick and should have very distinct gān (甘) and húigān(回甘) on the tongue and cheeks, which together induces salivation and leaves a "feeling" in the back of the throat.

- Spent tea: Whole leaves and leaf bud systems should be easily seen and picked out of the wet spent tea, with a limited amount of broken fragments. Twigs, and the fruits of the tea plant should not be found in the spent tea leaves, however animal (and human) hair, strings, rice grains and chaff may occasionally be included in the tea. The leaves should not crumble when rubbed, and with ripened pu-erh, it should not resemble compost. Aged raw puerh should have leaves that unfurl when brewed while leaves of most ripened puerh will generally remain closed.

- Made from high quality material

- Processed skillfully

- Stored properly over the years

- ^ Among many of the minority groups of China’s southwest, the Chinese character 鉧 is used to indicate cauldrons or pots.[41] The original transliteration of this character in The Famous Tea Mountains of Southern Yunnan, however, is "boa".[12]

- ^ Zhen, Shen (2004-02-02), "Qing Dynasty tea to be auctioned", China Daily

- ^ ""Han"". Puerh History http://www.artoftea.com, Art of Tea (June 14, 2006)

- ^ Mike Petro, ""Pu-erh History and Culture""., Pu-Erh.net (May 7, 2006)

- ^ a b c d e f Chan, Kam Pong (November 2006). First-Step to Chinese Puerh Tea (簡易中國普洱茶). Taipei, Taiwan: WuShing Books Publications Co. Ltd.. ISBN 978-957-8964-33-4.

- ^ Jonathan Sielaff, ""Making Mao Cha""., TaoofTea.com

- ^ a b JinYuXuan Teahouse, ""Talks about Black (Shou/Ripe) Pu-erh""., Teatalk101 (January 23 and January 29, 2006)

- ^ 陈可可, 朱宏涛, 王东, 张颖君, 杨崇仁. (2006). 普洱熟茶后发酵加工过程中曲霉菌的分离和鉴定/Isolation and Identification of Aspergillus Species from the Post Fermentative Process of Pu-Er Ripe Tea. 云南植物研究/ACTA BOTANICA YUNNANICA. (28)2. pp. 123-126 (Chen Keke, et al.)

- ^ ""Meng Hai Tea Factory – A Very Short History""., Dan Da Tee Man (March 23, 2006)

- ^ a b c d Mike Petro, ""Puerh Factories"". Pu-Erh.net

- ^ 叶伟, "" 纯正的云南普洱茶真正的干仓普洱茶"".www.ynttc.com

- ^ a b c d ""The Famous Tea Mountains of Southern Yunnan""., www.taooftea.com (Oct 25, 2006)

- ^ a b 普洱茶故乡–西双版纳、中国普洱茶, ""古“六大茶山”概况""., www.puerh.cn (Oct 25, 2006)

- ^ Guang Lee, " ""Guang Yun Gong Beeng""., Hou De Asian Art (October 7, 2005)

- ^ Shen Jingting (2009-06-15). ""Tempest over tea: What is the true Puer?"". China Daily. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ Mike Petro, ""Puerh is truly unique in many ways""., Pu-Erh.net (September 1, 2006)

- ^ Mike Petro, ""Aging"". Pu-erh LJ Community (February 3, 2006)

- ^ Sebastien Leseine, ""2005 Haiwan Lao Tong Zhi Label"". Jing Tea Shop

- ^ a b c d Guang Lee, ""Pu-erh Information"". Hou De Asian Art

- ^ Sebastien Leseine, ""How to store your pu-erh tea"". Jing Tea Shop(2005)

- ^ Ref tea article, ""Over Emphasizing the Importance of Age"". Puerh Cha

- ^ Guang Chung Lee (2006). ""The Varieties of Formosa Oolong"". Art of Tea. Retrieved 2006-12-12., Issue 1 http://www.the-art-of-tea.com

- ^ a b Mike Petro, ""How to Age"". Pu-Erh.net (May 7, 2006)

- ^ Puerh, Best, Electronics, Semiconductors, Electronic Component, Electronic Component Distributor, Semiconductor Industry, Semiconductor Equipment, Electronic Part

- ^ Teahub.com ""Authentic Old Pu-erh Tea"".

- ^ Hakim I.A., Alsaif M.A., Alduwaihy M., Al-Rubeaan K., Al-Nuaim A.R., Al-Attas O.S., (2002), "Tea Consumption and the Prevalence of Coronary Heart Disease in Saudi Adults: Results from A Saudi National Study", Preventive Medicine

- ^ [1] Chi-Hua Lua, Lucy Sun Hwang "Polyphenol contents of Pu-Erh teas and their abilities to inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis in Hep G2 cell line", Food Chemistry, Vol. 111, No. 1, (Nov. 1, 2008), pp. 67-71.

- ^ [2] Chiang, Chun-Te; Weng, Meng-Shih; Lin-Shiau, Shoei-Yn; Kuo, Kuan-Li; Tsai, Yao-Jen; Lin, Jen-Kun, "Pu-erh Tea Supplementation Suppresses Fatty Acid Synthase Expression in the Rat Liver Through Downregulating Akt and JNK Signalings as Demonstrated in Human Hepatoma HepG2 Cells",Oncology Research Featuring Preclinical and Clinical Cancer Therapeutics, Vol. 16, No. 3, (2006), pp. 119-128(10).

- ^ [3] She-Ching Wu, Gow-Chin Yen, Bor-Sen Wang, Chih-Kwang Chiu, Wen-Jye Yen, Lee-Wen Chang, Pin-Der Duh, "Antimutagenic and antimicrobial activities of pu-erh tea", LWT – Food Science and Technology, Vol. 40, No. 3, (Apr. 2007), pp. 506-512.

- ^ Sean Paajanen,"" Pu-erh Tea""., holymtn.com (Dec 12, 2006)

- ^ Lin, Jen-Kun; Shoei-Yn Lin-Shiau (September 28, 2005). "Mechanisms of hypolipidemic and anti-obesity effects of tea and tea polyphenols". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research (Weinheim: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA) 50 (2): 211–217. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200500138.

- ^ Cao J., Zhao Y., Liu J., (1998), "Safety evaluation and fluorine concentration of Pu’er brick tea and Bianxiao brick tea" Food Chem. Toxicol. 36(12):1061-1063

- ^ Jin Cao, Xuexin Bai, Yan Zhao, Jianwei Liu, Dingyou Zhou, Shiliang Fang, Ma Jia, Jinsheng Wu, (1996), "The Relationship of Fluorosis and Brick Tea Drinking in Chinese Tibetans", Environmental Health Perspectives, 104(12)

- ^ Cao J., Zhao Y., Liu J., (1997), "Brick tea consumption as the cause of dental fluorosis among children from Mongol, Kazak and Yugu populations in China" Food Chem. Toxicol. 35(8):827-833

- ^ Andrew Jacobs, ""A County In China Sees Its Fortunes In Tea Leaves Until a Bubble Bursts"". New York Times. January 17, 2009.

- ^ 户崎哲彦, 2001,"钴鉧"不是熨斗而是釜锅之属—柳宗元的文学成就与西南少数民族的语言文化, 柳州师专学报 (On "Gumu" Not Being an Iron but a Category of Cauldron or Pot)

- Babelcarp provided much of the terminology and characters in this article.

- Pu-erh Tea Community: Jargon also provided some translation help.

Introduction and history

Pu-erh tea is traditionally made with leaves from old wild tea trees of a variety known as "broad leaf tea" (Traditional: 大葉 Simplified: 大叶, dà yè) or Camellia sinensis var. assamica, which is found in southwest China as well as the bordering tropical regions in Burma, Vietnam, Laos, and the very eastern parts of India. The shoots and young leaves from this varietal are often covered with fine hairs, with the pekoe (two leaves and a bud) larger than other tea varietals. The leaves are also slightly different in chemical composition, which alter the taste and aroma of the brewed tea, as well as its desirability for aging. Due to the scarcity of old wild tea trees, pu-erh made using such trees blended from different tea mountains of Yunnan are highly valued, while more and more connoisseurs are seeking pu-erh with leaves taken from a single tea mountain’s wild forests. The history of pu-erh tea can be traced back to the Eastern Han Dynasty.[2]

Pu-erh is well known for the fact that it is a compressed tea and also that it typically ages well to produce a pleasant drink. Through storage, the tea typically takes on a darker colour and mellower flavour characteristics. Often pu-erh leaves are compressed into tea cakes or bricks, and are wrapped in various materials, which when stored away from excessive moisture, heat, and sunlight help to mature the tea. Pressing of pu-erh into cakes and aging the tea cakes possibly originated from the natural aging process that happened in the storerooms of tea drinkers and merchants, as well as on horseback caravans on the Ancient tea route (茶馬古道; pinyin: chámǎ gǔdaò) that was used in ancient Yunnan to trade tea to Tibet and more northern parts of China.[3] Compression of the tea into dense bulky objects likely eased horseback transport and reduced damage to the tea.

Production

All types of pu-erh tea are created from máochá(毛茶), a mostly unoxidized green tea processed from a "large leaf" variety of Camellia sinensis found in the mountains of southern Yunnan. Maocha can undergo "ripening" for several months prior to being compressed to produce ripened pu-erh (also commonly known as "cooked pu-erh"), or be directly compressed to produce raw pu-erh.

While unaged and unprocessed raw pu-erh is technically a type of green tea, ripened or aged raw pu-erh has occasionally been mistakenly categorised as a subcategory of black tea due to the dark red colour of its leaves and liquor. However, pu-erh in both its ripened or aged forms has undergone secondary oxidization and fermentation caused both by organisms growing in the tea as well as from free-radical oxidation, thus making it a unique type of tea.

In China, where fully-oxidised tea ("black tea") is known as "red tea," pu-erh is indeed classified as a "black tea" (defined as post-fermented), something which is resented by some who argue for a separate category for pu-erh as many other black teas tend to be of lower standard and status.

Raw pu-erh and Máochá

After picking appropriate tender leaves, the first step in making raw or ripened pu-erh is converting the leaf to máochá (青毛茶 or 毛茶; literally, "light green rough tea" or "rough tea" respectively). Plucked leaves are handled gingerly to prevent bruising and unwanted oxidation. Weather permitting, the leaves are then spread out in the sun or a ventilated space to wilt and remove some of the water content.[4] On overcast or rainy days, the leaves will be wilted by light heating, a slight difference in processing that will affect the quality of the resulting maocha and pu-erh. The wilting process may be skipped altogether depending on the tea processor.

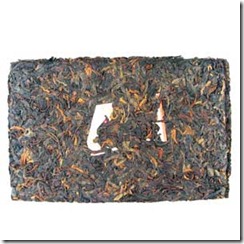

Relatively young Raw pu-erh. Note the grey and dark green tones.

The leaves are then dry pan-fried using a large wok in a process called "kill green" (殺青; pinyin: shā qīng), which arrests enzyme activity in the leaf and prevents further oxidation. With enzymatic oxidation halted, the leaves can then be rolled, rubbed, and shaped through several steps into strands. The shaped leaves are then ideally dried in the sun and then manually picked through to remove bad leaves.[4] Once dry, máochá can be sent directly to the factory to be pressed into raw pu-erh, or to undergo further processing to make ripened pu-erh.[5] Sometimes maocha is aged uncompressed and sold at its maturity as aged loose-leaf raw pu-erh.

Raw pu-erh tea (Chinese: 生茶; pinyin: shēngchá or Chinese: 青茶; pinyin: qīngchá), also known as "uncooked pu-erh" or "green pu-erh," is simply máochá tea leaves that have been compressed into its final form without additional processing.

Ripe pu-erh

Ripened pu-erh. Note the orange-brown tone of the lighter leaves due to oxidation/fermentation.

Ripened pu-erh tea (Chinese: 熟茶; pinyin: shúchá) is pressed maocha that has been specially processed to imitate aged raw pu-erh. Although it is more commonly known as "cooked pu-erh," the process does not actually employ cooking to imitate the aging process. The term may come about due to inaccurate transliteration due to the dual meaning of "shú" (熟) as both "fully cooked" and "fully ripened"。

The process used to convert máochá into ripened pu-erh is a recent invention that manipulates conditions to approximate the result of the aging process by prolonged bacterial and fungal fermentation in a warm humid environment under controlled conditions, a technique called wòdūi (渥堆, "wet piling" in English), which involves piling, dampening, and turning the tea leaves in a manner much akin to composting.[6]

The piling, wetting, and mixing of the piled máochá ensures even fermentation.[6] The bacterial and fungal cultures found in the fermenting piles were found to vary widely from factory to factory throughout Yunnan, consisting of multiple strains of Aspergillus spp.,Penicillium spp., yeasts, as well as wide range of other microflora.

Control over the multiple variables in the ripening process, particularly humidity and the growth of Aspergillus spp., is key in producing ripened pu-erh of high quality.[7] Poor control in fermentation/oxidation process can result in bad ripened pu-erh, characterized by badly decomposed leaves and an aroma and texture reminiscent of compost. The ripening process typically takes anywhere from half a year to one year after it has begun.

As such, a ripened pu-erh produced in early 2004 will be pressed in the winter of 2004/2005, and appear on the market between late 2005 or early 2006.

This process was first developed in 1972 by Menghai Tea Factory and Kunming Tea Factory[8] to imitate the flavor and color of aged raw pu-erh. This technique was an adaptation of "wet storage" techniques that were being used by merchants to falsify the age of their teas. Mass production of ripened pu-erh began in 1975. It can be consumed without further aging, though it can also be stored to "air out" some of the less savory flavors and aromas acquired during fermentation. The tea is often compressed but is also common in loose form. Some collectors of pu-erh believe that ripened pu-erh should not be aged for more than a decade.

Pressing

A "Hand-pressed" pu-erh bing, revealing the hollow knot dimple in its rear face and an uneven edge

To produce pu-erh many additional steps are needed prior to the actual pressing of the tea. First, a specific quantity of dry máochá or ripened tea leaves pertaining to the final weight of the bingcha is weighed out. The dry tea is then lightly steamed in perforated cans to soften and make it more tacky. This will allow it to hold together and not crumble during compression. A ticket, called a "Nèi fēi" (内飞) or additional adornments, such as coloured ribbons, are placed on or in the midst of the leaves and inverted into a cloth bag or wrapped in cloth. The pouch of tea is gathered inside the cloth bag and wrung into a ball, with the extra cloth tied or coiled around itself. This coil or knot is what produces the dimpled indentation at the reverse side of a tea cake when pressed. Depending on the shape of pu-erh being produced, a cotton bag may or may not be used. For instance, brick or square teas often are not compressed using bags.[9][10]

Depending on the desired product and speed, from quickest and tightest to slowest and loosest, pressing can either be done by:

A hydraulic press, which forces the tea into a metal form that is occasionally decorated with a motif in sunken-relief. Due to its efficiency, this method is commonly used to make all forms of pressed pu-erh. Tea can be pressed in the press either with or without it being bagged, with the latter done by utilizing a metal mould. Tightly compressed bing, formed directly into a mold without bags using this method are known as tié bǐng (鐵餅, literally "iron cake/puck") due to its density and hardness. It is believed that the taste of densely compressed raw pu-erhs can benefit from careful aging for up to several decades.

A lever press, which was operated by hand for tight pressings and has largely been replaced by the modern hydraulic press.

A large heavy stone, carved into the shape of a short cylinder with a handle, simply weighs a bag of tea down onto a wooden board. The tension from the bag and the weight of the stone together gives the tea its rounded and sometimes non-uniformed edge. Due to the manual labor involved, this method of pressing is often referred to as: "Hand" or "Stone-pressing," and is how many artisanal pu-erh bing are still manufactured.

Pressed pu-erh is removed from the cloth bag and placed on latticed shelves where they are allowed to air dry, which depending on the wetness of the pressed cakes may take several weeks or months.[4] The pu-erh cakes are then individually wrapped by hand, and packaged in larger units for trade or commerce.

Classification

Aside from vintage year, pu-erh tea can be classified in a variety of ways: by shape, processing method, region, cultivation, grade, and season.

Shape

Pu-erh is compressed into a variety of shapes. Other lesser seen forms include, stacked "melon pagodas", pillars, calabashes, yuanbao, and small bricks (2–5 cm in width). Pu-erh is also compressed into the hollow centers of bamboo stems or packed and bound into a ball inside the peel of various citrus.

|

Image |

Common name |

Description |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

Bing, Beeng, Cake, or Disc

Chinese

|

A round, flat, disc or hockey puck-shaped tea. Size ranges from as small as 100g to as large as 5 kg or more, with 357g, 400g, and 500g being the most common. Depending on the pressing method, the edge of the disk can be rounded or perpendicular. Also commonly known as Qīzí bǐngchá (七子餅茶, literally "Seven units cake tea") because seven of the bing are packaged together at a time for sale or transport. |

|||

|

|

Tuocha, Bowl, or Nest

|

A convex knob-shaped tea with size ranging from 3g to 3 kg or more, with 100g, 250g, 500g being the most common. The name for "tuocha" is believed to have originated from the round, top-like shape of the pressed tea or from the old tea shipping and trading route of the Tuojiang River.[11] In ancient times, tuocha cakes may have had holes punched through the center so that they could be tied together on a rope for easy transport. |

|||

|

|

Brick

|

A thick rectangular block of tea, usually in 100g, 250g, 500g, and 1000g sizes. Zhuancha bricks are the traditional shape that was used for ease of transport along the Ancient tea route by horse caravans. |

|||

|

|

Square

|

A flat square of tea, usually in 100g or 200g sizes. They often contain words that are pressed into the square. |

|||

|

|

Mushroom

|

Literally meaning "tight tea," the tea is shaped much like túocha, but with a stem rather than a convex hollow. This makes them quite similar in form to a mushroom. Pu-erh tea of this shape is generally produced for Tibetanconsumption, and is usually 250g or 300g. |

|||

|

|

Melon, or Gold melon

|

A shape similar to tuóchá, but larger in size with a much thicker body that is decorated with pumpkin-like "stripes". This shape was created for the famous "Tribute tea" (貢茶) that was made expressly for the Qing Dynasty Emperorsfrom the best tea leaves of Yiwu Mountain. Larger specimens of this shape are sometimes called "Human-head tea" (人頭茶) due in part to its size and shape, as well as the fact that in the past it was often presented in court in a similar manner to severed heads of enemies or criminals. |

|||

|

|

Loose Leaf

|

Maocha that is aged uncompressed and sold at its maturity as aged loose-leaf raw pu-erh. |

|||

|

|

Packed Tangerine Peel. Ju Pu

|

Pu-erh leaves stuffed into a whole Tangerine Peel. The leaves are packed into the fruit wet, and then dried under the sunlight. After that, the packed tangerine teas are then stored in a cool dry location, allowing the tea to ferment and dry within the tangerine peel.

While drying the pu-erh tea absorb the flavor of tangerine. |

|||

|

|

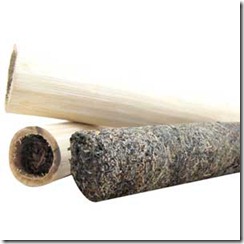

Tong Cha. Packed in Bamboo Tube.

|

Raw tea leaves have been forced down in the the open end of the aromatic bamboo section, then bamboo sections are barbecued in a wood fire. As the bamboo dries in the fire the special aroma intermingles with the Pu-erh inside. |

Process and oxidation

Although pu-erh teas are often collectively classified in Western and East Asian tea markets as post-fermentation or black teas, respectively, pu-erh teas in actuality can be placed in three types of processing methods, namely: green tea, fermented tea, and secondary-oxidation/fermentation tea.

Pieces of a 1970’s "Green/raw" Guang yun tribute teacake(廣雲貢餅). Note that aging has turned the previously green leaves of this cake to a brownish black colour

Pu-erh can be green teas if they are lightly processed before being pressed into cakes. Such pu-erh is referred to as maocha if unpressed and as "green/raw pu-erh" if pressed. While not always palatable, they are relatively cheap and are known to age well for up to 20 or 30 years. Pu-erh can also be a fermented tea if it undergoes slow processing with fermenting microbes for up to a year. This pu-erh is referred to as "ripened/cooked pu-erh", and has a mellow flavour and is readily drinkable. Aged pu-erhs are secondary-oxidation and post-fermentation teas. If aged from green pu-erh, the aged tea will be mellow in taste but still clean in flavour.

According to the production process, four main types of pu-erh are commonly available on the market:

Maocha: Green pu-erh leaves that are sold in loose form. The raw material for making pressed pu-erhs. Badly processed maocha will result in an inferior pu-erh.

Green/raw pu-erh: Pressed maocha that has not undergone additional processing. Quality green pu-erh is highly sought by collectors.

Ripened/cooked pu-erh: Pressed maocha that has undergone fermentation in the ripening process for up to a year. Badly fermented maocha will create a muddy tea with fishy and sour flavours indicative of inferior aged pu-erhs.

Aged raw pu-erh: A tea that has undergone a slow secondary oxidation and a certain degree of microbial fermentation. Although all types of pu-erh can be aged, it is typically the pressed raw pu-erhs that are most highly regarded, since aged maocha and ripened pu-erh both lack a "clean" and "assertive" taste.

Regions

Yunnan

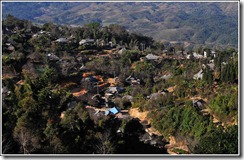

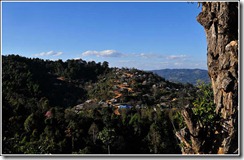

Yunnan province produces the vast majority of pu-erh tea. Indeed, the province is the source of the tea’s name, Pu’er Hani and Yi Autonomous County. Pu-erh is produced in almost every county and prefecture in the province, but the most famous pu-erhareas are known as the Six Famous Tea Mountains (Chinese: 六大茶山; pinyin: liù dà chá shān)

[edit]Six famous tea mountains

The six famous tea mountains are a group of mountains in Xishuangbanna that are renowned for their climates and environments, which not only provide excellent growing conditions for pu-erh, but also produce unique taste profiles (akin to terroir in wine) in the produced pu-erh tea. Over the course of history, the designated mountains for the tea mountains have either been changed[12] or listed differently.[13][14][15]

In the Qing dynasty government records for pu-erh (普洱府志), the oldest historically designated mountains were said to be named after six commemorative items that were left in the mountains by Zhuge Liang,[14] and using the Chinese characters of the native language of the region.[16] These mountains are all located northeast of the Lancang River (Mekong) in relatively close proximity to one another.

The mountains’ names, in the Standard Mandarin character pronunciation are:

Southwest of the river there are also six famous tea mountains that are lesser known from ancient times due to their isolation by the river.[15] They are:

For various reasons, by the end of the Qing dynasty or beginning of the ROC period, tea production in these mountains dropped drastically, either due to large forest fires, over-harvesting, prohibitive imperial taxes, or general neglect.[12][16] To revitalize tea production in the area, the Chinese government in 1962 selected a new group of six famous tea mountains that were named based on the more important tea producing mountains at the time, including Youle mountain from the original six.[12]

[edit]Other areas of Yunnan

Many other areas of Yunnan also produce pu-erh tea. Yunnan prefectures that are major producers of pu-erh include Lincang, Dehong, Simao, Xishuangbanna, and Wenshan.

Other tea mountains famous in Yunnan include among others:

Region is but one factor in assessing a pu-erh tea, and pu-erh from any region of Yunnan is as prized as any from the six famous tea mountains if it meets other criteria, such as being wild growth, hand-processed tea.

Other provinces

While Yunnan produces the majority of pu-erh, other regions of China, including Hunan and Guangdong, have also produced the tea. The Guangyun Gong cake, for example, featured a blend of Yunnan and Guangdong máochá, and the most recent production of these cakes contains mostly from the latter.[17]

In late 2008, the Chinese government approved a standard declaring Puer tea as a "product with geographical indications", which would restrict the naming of tea as Puer to tea produced within specific regions of the Yunnan province. The standard has been disputed, particularly by producers fromGuangdong.[18]

Other regions

In addition to China, border regions touching Yunnan in Vietnam, Laos, and Burma are also known to produce pu-erh tea, though little of this makes its way to the Chinese or international markets.

Cultivation

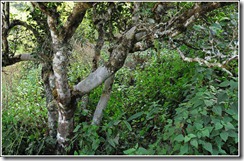

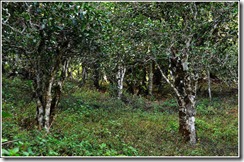

Perhaps equally or even more important than region or even grade in classifying pu-erh is the method of cultivation. Pu-erh tea can come from three different cultivation methods:

Plantation bushes (guànmù, 灌木; taídì, 台地): Cultivated tea bushes, from the seeds or cuttings of wild tea trees and planted in relatively low altitudes and flatter terrain. The tea produced from these plants are considered inferior due to the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizer in cultivation, and the lack of pleasant flavours, and the presence of harsh bitterness and astringency from the tea.

"Wild arbor" trees (yěfàng, 野放): Most producers claim that their pu-erh is from wild trees, but most use leaves from older plantations that were cultivated in previous generations that have gone feral due to the lack of care. These trees produce teas of better flavour due to the higher levels ofsecondary metabolite produced in the tea tree. As well, the trees are typically cared for using organic practices, which includes the scheduled pruning of the trees in a manner similar to pollarding. Despite the good quality of their produced teas, "wild arbor" trees are not as prized as the truly wild trees.

Wild trees (gŭshù, 古树; literally "old tree"): Teas from old wild trees, grown without human intervention, are the highest valued pu-erh teas. Such teas are valued for having deeper and more complex flavors, often with camphor or "mint" notes, said to be imparted by the many camphor trees that grow in the same environment as the wild tea trees. Young raw pu-erh teas produced from the leaf tips of these trees also lack overwhelming astringency and bitterness often attributed to young pu-erh.

Determining whether or not a tea is wild is a challenging task, made more difficult through the inconsistent and unclear terminology and labeling in Chinese. Terms like yěshēng (野生; literally "wild" or "uncultivated"), qiáomù (乔木; literally "tall tree"), yěshēng qiáomù (野生乔木; literally "uncultivated trees"), and gǔshù are found on the labels of cakes of both wild and "wild arbor" variety, and on blended cakes, which contain leaves from tea plants of various cultivations. These inconsistent and often misleading labels can easily confuse uninitiated tea buyers regardless of their grasp of the Chinese language. As well, the lack of specific information about tea leaf sources in the printed wrappers and identifiers that come with the pu-erh cake makes identification of the tea a difficult task. Pu-erh journals and similar annual guides such as The Profound World of Chi Tse, Pu-erh Yearbook, and Pu-erh Teapot Magazine contain credible sources for leaf information. Tea factories are generally honest about their leaf sources, but someone without access to tea factory or other information is often at the mercy of the middlemen or an unscrupulous vendor. Many pu-erh aficionados seek out and maintain relationships with vendors who they feel they can trust to help mitigate the issue of finding the "truth" of the leaves.

Sadly, even in the best of circumstances, when a journal, factory information, and trustworthy vendor all align to assure a tea’s genuinely wild leaf, fakes fill the market and make the issue even more complicated. Because collectors often doubt the reliability of written information, some believe certain physical aspects of the leaf can point to its cultivation. For example, drinkers cite the evidence of a truly wild old tree in a menthol effect ("camphor" in tea specialist terminology) supposedly caused by the Camphor laurel trees that grow amongst wild tea trees in Yunnan’s tea forests.[19] As well, the presence of thick veins and sawtooth-edged on the leaves along with camphor flavor elements and taken as signifiers of wild tea.[20]

Grade

Pu-erh can be sorted into ten or more grades. Generally, grades are determined by leaf size and quality, with higher numbered grades meaning older/larger, broken, or less tender leaves. Grading is rarely consistent between factories, and first grade tea leaves may not necessarily produce first grade cakes. Different grades have different flavors, and many bricks feature a blend of several grades chosen to balance flavors and strength.[21]

Season

Harvest season also plays an important role in the flavor of pu-erh. Spring tea is the most highly valued, followed by fall tea, and finally summer tea. Only rarely is pu-erh produced in winter months, and often this is what is called "early spring" tea, as harvest and production follows the weather pattern rather than strict monthly guidelines.

Tea factories

A Menghai microprinted ticket, first appearing in 2006

Factories are generally responsible for the production of pu-erh teas. While some individuals oversee smaller higher-end productions, such as the Xizihao and Yanqinghao brands,[20] the majority of tea on the market is compressed by factories or tea groups. Until recently, factories were all state owned and under the supervision of the China National Native Produce & Animal Byproducts Import & Export company (CNNP), Yunnan Branch. Kunming Tea Factory, Menghai Tea Factory, Pu’er Tea Factory and Xiaguan Tea Factoryare the most notable of these state owned factories. While CNNP still operates today, few factories are state-owned, and CNNP contracts out many productions to privately owned factories.

Different tea factories have garnered good reputations. Menghai Tea Factory and Xiaguan Tea Factory, which date from the 1940s, have enjoyed good reputations, but these factories now face competition from many of the newly emerging private factories. For example,Haiwan Tea Factory, founded by former Menghai Factory owner Zhou Bing Liang in 1999,[22] enjoys a good reputation, as does Changtai Tea Group, Mengku Tea Company, and other new tea makers formed in the 1990s. However, due to production inconsistencies and variations in manufacturing techniques, the reputation of a tea company or factory can vary depending on the year or the specific cakes produced during a year.

The producing factory is often the first or second item listed when referencing a pu-erh cake, the other being the year of production.

Recipes

Tea factories, particularly formerly government-owned factories, produce many cakes by its recipe tea blends, indicated by a recipe number. Recipe numbers consists of four-digits. The first two digits represent the year the recipe was first produced, the third digit the grade of leaves used in the recipe, and the last digit represents the factory. 7542, for example, would be a recipe from 1975 using fourth-grade tea leaf made by Menghai Tea Factory (represented by 2). There are also those who believe that the third number indicates a recipe for a particular production year.[9]

Factory numbers (fourth digit in recipe):

Tea of all shapes can be made by numbered recipe. Not all recipes are numbered, and not all cakes are made by recipe. The term "recipe," it should be added, does not always indicate consistency, as the quality of some recipes change from year-to-year, as do the contents of the cake. Perhaps only the factories producing the recipes really know what makes them consistent enough to label by these numbers.

Occasionally, a three digit code is attached to the recipe number by hyphenation. The first digit of this code represents the year the cake was produced, and the other two numbers indicate the production number within that year. For instance, the seven digit sequence 8653-602, would indicate thesecond production in 2006 of factory recipe 8653. Some productions of cakes are valued over others because production numbers can indicate if a tea was produced earlier or later in a season/year. This information allows one to be able to single out tea cakes produced using a better batch ofmáochá.

Tea packaging

Pu-erh tea is specially packaged for trade, identification, and storage. These attributes are used by tea drinkers and collectors to determine the authenticity of the pu-erh tea.

Individual cakes

Typical contents of a wrapped Bĭngchá

Pu-erh tea cakes, or Bĭngchá, are almost always sold with[23] a:

Wrapper: Made usually from thin cotton cloth or cotton paper and shows the tea company/factory, the year of production, the region/mountain of harvest, the plant type, and the recipe number. The wrapper can also contain decals, logos and artwork. Occasionally, more than one wrapper will be used to wrap a pu-erh cake.

Nèi fēi (内飞 or 內飛): A small ticket originally stuck on the tea cake but now usually embedded into the cake during pressing. It is usually used as proof, or a possible sign, to the authenticity of the tea. Some higher end pu-erh cakes have more than one nèi fēi embedded in the cake. The ticket usually indicates the tea factory and brand.

Nèi piào (内票): A larger description ticket or flyer packaged loose under the wrapper. Both aid in assuring the identity of the cake. It usually indicates factory and brand. As well, many nèi piào contain a summary of the tea factories’ history and any additional laudatory statements concerning the tea, from its taste and rarity, to its ability to cure diseases and affect weight loss.

Bĭng: The tea cake itself. Tea cakes or other compressed pu-erh can be made up of two or more grades of tea, typically with higher grade leaves on the outside of the cake and lower grades or broken leaves in the center. This is done to improve the appearance of the tea cake and improve its sale. Predicting the grade of tea used on the inside takes some effort and experience in selection. However, the area in and around the dimple of the tea cake can sometimes reveal the quality of the inner leaves.

A tŏng of recipe 7742 tea cakes wrapped in bamboo shoot husks

Recently, nèi fēi have become more important in identifying and preventing counterfeits. Menghai Tea Factory in particular has begun microprinting and embossing their tickets in an effort to curb the growth of counterfeit teas found in the marketplace in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Some nèi fēi also include vintage year and are production-specific to help identify the cake and prevent counterfeiting through a surfeit of different brand labels.

Wholesale

When bought in large quantities, pu-erh tea is generally sold in stacks, referred to as a tŏng (筒), which are wrapped in bamboo shoot husks, bamboo stem husks, or coarse paper. Some tongs of vintage pu-erh will contain a tŏng piào (筒票), or tong ticket, but it is less common to find them in productions past the year 2000.[4] The number of bĭngchá in a tŏng varies depending on the weight of individual bĭngchá. For instance one tŏng can contain:

Seven 357g-500g bĭngchá,

Five 250g mini-bĭngchá

Ten 100g mini-bĭngchá

Twelve tŏng are referred to as being one jiàn (件), although some producers/factories vary how many tŏng equal one jiàn. A jiàn of tea, which is bound together in a loose bamboo basket, will usually have a large batch ticket (大票; pinyin: dàpiào) affixed to its side that will indicate information such as the batch number of the tea in a season, the production quantities, tea type, and the factory where it was produced.[4]

Aging and storage

Pu-erh teas of all varieties, shapes, and cultivation can be aged to improve their flavour, but the tea’s physical properties will affect the speed of aging as well as its quality.

These properties include:

Leaf quality: The most important factor, arguably, is leaf quality. Maocha that has been improperly processed will not age to the level of finesse as properly processed maocha. The grade and cultivation of the leaf also greatly affect its quality, and thus its aging.

Compression: The tighter a tea is compressed, the slower it will age. In this respect, looser hand- and stone-pressed pu-erhs will age more quickly than denser hydraulic-pressed pu-erh.

Shape and size : The more surface area, the faster the tea will age. Bingcha and zhuancha thus age more quickly than golden melon, tuocha, or jincha. Larger bingcha age slower than smaller bingcha, and so forth.

Just as important and the tea’s properties, environmental factors for the tea’s storage also affect how quickly and successfully a tea ages. They include:

Air flow: Regulates the oxygen content surrounding the tea and removes odours from the aging tea. Dank, stagnant air will lead to dank, stale smelling aged tea. Wrapping a tea in plastic will eventually arrest the aging process.

Odours: Tea stored in the presence of strong odours will acquire them, sometimes for the duration of their "lifetime." Airing out pu-erh teas can reduce these odours, though often not completely.

Humidity : The higher the humidity, the faster the tea will age. Liquid water accumulating on tea may accelerate the aging process but can also cause the growth of mold or make the flavour of the tea less desirable. 60-85% humidity is recommended.[24] It is argued whether tea quality is adversely affected if it is subjected to highly fluctuating humidity levels.

Sunlight: Tea that is exposed to sunlight dries out prematurely, and often becomes bitter.

Temperature: Teas should not be subjected to high heat since undesirable flavours will develop. However at low temperatures, the aging of pu-erh tea will slow down drastically. It is argued whether tea quality is adversely affected if it is subjected to highly fluctuating temperature.

When preserved as part of a tong, the material of the tong wrapper, whether it is made of bamboo shoot husks, bamboo leaves, or thick paper, can also affect the quality of the aging process. The packaging methods change the environmental factors and may even contribute to the taste of the tea itself.

Further to what has been mentioned it should be stressed that a good well-aged Puerh tea is not evaluated by its age alone. Like all things in life, there will come a time when a Puerh teacake reaches its peak before stumbling into a decline. Due to the many recipes and different processing method used in the production of different batches of Puerh, the optimal age for each age will vary. Some may take 10 years while others 20 or 30+ years. It is important to check the status of ageing for your teacakes to know when they peaked so that proper care can be given to halt the ageing process.[25]

Raw pu-erh

Over time, raw pu-erh acquires an earthy flavor due to slow oxidation and other, possibly microbial processes. However, this oxidation is not analogous to the oxidation that results in green, oolong, or black tea, because the process is not catalyzed by the plant’s own enzymes but rather by fungal, bacterial, or autooxidation influences. Pu-erh flavors can change dramatically over the course of the aging process, resulting in a brew tasting strongly earthy but clean and smooth, reminiscent of the smell of rich garden soil or an autumn leaf pile, sometimes with roasted or sweet undertones. Because of its ability to age without losing "quality", well aged good pu-erh gains value over time in the same way that aged roasted oolong does.[26]

Raw pu-erh can undergo "wet storage" (shīcāng, 湿仓) and "dry storage" (gāncāng 干仓), with teas that have undergone the latter ageing more slowly, but thought to show more complexity. Dry storage involves keeping the tea in "comfortable" temperature and humidity, thus allowing the aging process to occur slowly. Wet Storage or "humid storage" refers to the storage of pu-erh tea in humid environments, such as those found naturally in Hong Kong, Guangzhou and, to a lesser extent, Taiwan.

The practice of "Pen Shui" 喷水 involves spraying the tea with water and allowing it dry off in a humid environment. This process speeds up oxidation and microbial conversion, which only loosely mimics the quality of natural dry storage aged pu-erh. "Pen Shui" 喷水 pu-erh not only does not acquire the nuances of slow aging, it can also be hazardous to drink because of mold, yeast, and bacteria cultures.[27]

Pu-erh properly stored in different environments can develop different tastes at different rates due to environmental differences in ambient humidity, temperature, and odours.[4] For instance, similar batches of pu-erh stored in the different environments of Taiwan and Hong Kong are known to age very differently. Because the process of aging pu-erh is a lengthy one and teas may change owners several times, a batch of pu-erh may undergo different aging conditions, even swapping wet and dry storage conditions, which can drastically alter the flavor of that tea. Raw pu-erh should not be stored at very high temperatures, or be exposed to direct contact with sunlight, heavy air flow, liquid water, or unpleasant smells, since such poor storage conditions can ruin even the best quality pu-erh.

Although low to moderate air flow is important for producing a good quality aged raw pu-erh, it is generally agreed by most collectors and connoisseurs that raw pu-erh tea cakes older than 30 years old should not be further exposed to "open" air since it would result in the loss of flavours or degradation in mouthfeel. The tea should instead be preserved by wrapping or hermetically sealing it in plastic wrapping or ideally glass.[28]

Ripe pu-erh

Since the ripening process was developed to imitate aged raw pu-erh, many arguments surround the idea of whether aging ripened pu-erh is desirable. Mostly, the issue rests on whether aging ripened pu-erh will, better or worse, alter the flavor of the tea.

It is often recommended to age ripened pu-erh to "air out" the unpleasant musty flavours and odours formed due to maocha fermentation. However, some collectors argue that keeping ripened pu-erh longer than 10 to 15 years makes little sense, stating that the tea will not develop further and possibly lose its desirable flavours. Others note that their experience has taught them that ripened pu-erh indeed does take on nuances through aging,[23] and point to side-by-side taste comparisons of ripened pu-erh of different ages. Though the storing period increases the value of the tea, it is not often that such actions will be taken as it is not economically efficient.[28]

Preparation

Preparation of pu-erh involves first separating a well-sized portion of the compressed tea for brewing. This can be done by flaking off pieces of the cake or by steaming the entire cake until it is soft from heat and hydration.[23] A pu-erh knife, which is similar to an oyster knife or a rigid letter opener, is used to pry large horizontal flakes of tea off the cake such as to minimize leaf breakage. Steaming is usually performed on smaller teas such as tuocha or mushroom pu-erh and involves steaming the cake until it can be rubbed apart and then dried. In both cases, a vertical sampling of the cake should be obtained since the quality of the leaves in a cake usually varies between the surface and the center of the cake.

Pu-erh is generally expected to be served Gongfu style, generally in Yixing teaware or in a type of Chinese teacup called a gaiwan. Optimum temperatures are generally regarded to be around 95 degree Celsius for lower quality pu-erhs and 85-89 degree Celsius for good ripened and aged raw pu-erh. Steeping times last from 12–30 seconds in the first few infusions, up to 2–10 minutes in the last infusions. The prolonged steeping techniques used by some western tea makers can produce dark, bitter, and unpleasant brews. Quality aged pu-erh can yield many more infusions, with different flavour nuances when brewed in the traditional Gong-Fu method.[29]

Because of the prolonged fermentation in ripened pu-erh and slow oxidization of aged raw pu-erh, these teas often lack the bitter, astringent properties of other tea types, and also can be brewed much stronger and repeatedly, with some claiming 20 or more infusions of tea from one pot of leaves.[30]On the other hand, young raw pu-erh is known and expected to be strong and aromatic, yet very bitter and somewhat astringent when brewed, since these characteristics are believed to produce better aged raw pu-erh.

Judging quality

Spent leaves of badly stored shou pu-erh. Note the crumbling leaf faces that are barely held together by leaf veins

Quality of the tea can be determined through inspecting the dried leaves, the tea liquor, or the spent tea leaves. The "true" quality of a specific batch of pu-erh can ultimately only be revealed when the tea is brewed and tasted.

Although, not concrete and sometimes dependent on preference, there are several general indicators of quality:

[edit]Practices

In Cantonese culture, pu-erh is known as po-lay (or bo-lay) tea. Among the Cantonese long settled in California, it is called bo-nay or po-nay tea. It is often drunk during dim sum meals, as it is believed to help with digestion. It is not uncommon to add dried osmanthus flowers, pomelo rinds, orchrysanthemum flowers into brewing pu-erh tea in order to add a light, fresh fragrance to the tea liquor. Pu-erh with chrysanthemum is the most common pairing, and referred as guk pou or guk bou (菊普; pinyin: jú pǔ). Pu-erh is considered to have some medicinal qualities.

Sometimes wolfberries are brewed with the tea, plumpening in the process.

Health

See also: Potential effects of tea on health

Drinking pu-erh tea is purported to reduce blood cholesterol[31]. This belief has been backed up by scientific studies not only demonstrating experimental results of lowered LDL cholesterol in rats, but discovering specific mechanisms through which chemicals in Pu-erh tea inhibit the synthesis of cholesterol.[32][33] Pu-erh tea has been shown to have antimutagenic and antimicrobial properties as well.[34]

It is also widely believed in Chinese cultures to counteract the unpleasant effects of heavy alcohol consumption. In traditional Chinese medicine, the tea is believed to invigorate the spleen and inhibit "dampness." In the stomach, it is believed to reduce heat and "descends qi".[35]

Pu-erh tea is widely sold as a weight loss tea or used as a main ingredient in such commercially prepared tea mixtures. Though there is as yet no empirically backed evidence as to how pu-erh might facilitate weight loss, there are widely proposed explanations include that the tea increases the drinker’s metabolism, or that the high tannin[dubious – discuss] content in the tea binds macronutrients and coagulate digestive enzymes, thus reducing nutrient absorption. Although evidence is still sparse, it has been shown that rats experience reduction in body weight, blood triglycerides, and blood cholesterol following a diet containing pu-erh tea.[36]

Some pu-erh brick tea has been found to contain very high levels of fluorine, because it is generally made from lesser quality older tea leaves and stems, which accumulate fluorine.[37] Its consumption has led to fluorosis (a form of fluoride poisoning that affects the bones and teeth) in areas of high brick tea consumption, such as Tibet.[38][39]

Investment

Pu-erh tea can generally improve in taste over time (due to natural secondary oxidation and fermentation).

Teas that can be aged finely are typically:

The common misconception is that all types of pu-erh tea will improve in taste—and therefore get more valuable as an investment item—as they get older. There are many requisite variables for a pu-erh tea to age beautifully. Further, the cooked (shou) pu-erh will not evolve as dramatically as the raw (sheng) type will over time from the secondary oxidation and fermentation.

As with wine, only the finely made and properly stored ones will improve and increase in value. Similarly, the percentage of those that will improve over a long period of time is only a small fraction of what is available in the market today.

Beginning in 2008, much of the Pu’er industry suffered a tremendous drop in prices. Consequently, many have lost their fortunes and some have even decided to stop selling, growing, or distributing Pu’er as a result of the financial loss plaguing many of those in the industry. Investment-grade Pu’er has witnessed declines in price as well, although not as drastically as those varieties which are more common.[40]

Notes

[edit]References

源文档 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pu-erh_tea#cite_note-JinYuXuan-5>

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png)